On the road with Reinhold Messner

Unbowed. Unbeaten. Unhinged? Three days with the many faces of the world’s greatest – and most controversial – mountaineer.

© Simon Ingram / Trail Magazine, 2012

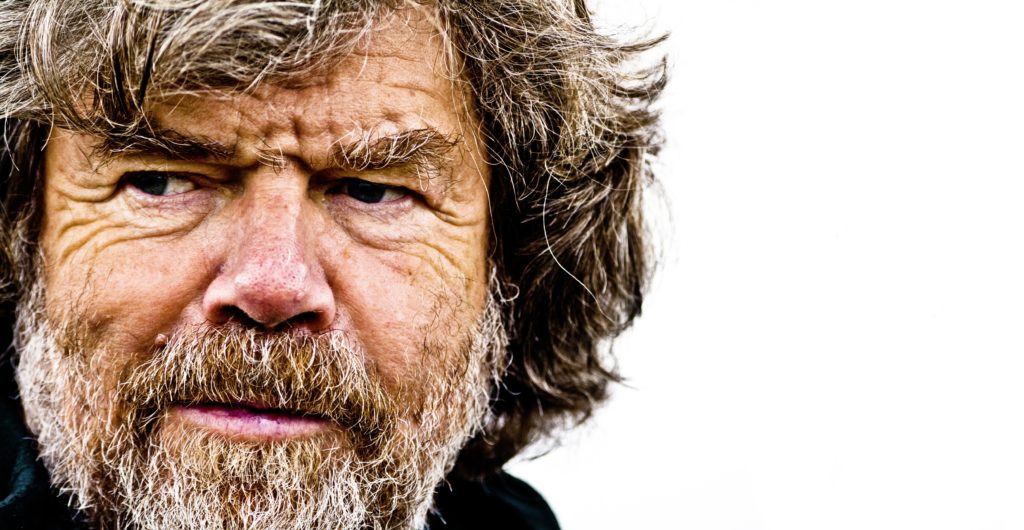

REINHOLD MESSNER IS MAD. Arms folded, he’s fidgeting and irritably watching flies. Behind us, some geese are making a racket. Inside the inn, his dinner is getting cold. His face is fixed in his trademark, hairy glare. It’s a look that says: ‘make this quick’.

We’re in Italy’s south Tyrol, above the town of Bruneck. if one of those geese was to shut up, take off and fly south-west about 10 miles over the Dolomites they would find Villnoss, where Reinhold was born. The spired massif flown over en route is the Geislerspitzen. like most of the dolomites in this sequestered region, it’s gorgeous, incredible, stupendous: an expletive of a mountain, elegant and brutal, seeming to defy gravity. This was Messner’s first mountain. He was five years old. It figures.

Trail has spent three days with Reinhold travelling through the region across which five newly completed museums bearing his name are poised. Installed in the ruins of mountaintop fortresses, like most of his challenges the Messner Mountain Museums are stunning, controversial and unique. Their creator hopes they reflect the relationship between man and mountain. I’m hoping they might give some insight into the mind of one of mountaineering’s most embattled and superhuman figures.

Reinhold the Mountaineer is the greatest of all time. He took what others had done in alpinism and smashed it, along the way redefining what was thought possible for a human. Along the way he’s taken the bullets of both mountaineer and celebrity: acclaim, injury, tragedy, fortune, envy, attack – leaving peers mouthing incredulous ‘how the hells’ in his wiry Italian shadow. As mountaineer Ed Viesturs put it: “after Messner, the mystery of possibility was gone; there remained only the mystery of whether you could do it.” As for Reinhold the Man, the answer is more complicated. Slight but cinematic of presence, his features peer sternly out of a crinkled, tanned window between big hair and beard. Some men who riff this look resemble Father Christmas; Reinhold looks like a wolf in a human costume.

You’ll hear he’s an arrogant badass, and his charisma wears this like a cape, tempting many excellent badass jokes. Reinhold Messner can slam revolving doors. Reinhold Messner died 10 years ago; death just hasn’t worked up the courage to tell him yet. Reinhold Messner doesn’t dial the wrong number; you answer the wrong phone, and so on. I’d love to tell you it’s all rubbish, and the man’s a teddy bear. But the 67-year-old knows his ability to own a room with his intensity, and wields it like a shotgun.

When he smiles at you, you feel like you can ask him anything. When he doesn’t – and fixes you with that stare of his – you’re afraid to open your mouth. He will not interview over the phone; he likes to look people in the eye. He’s blunt and loves to shock, occasionally firing something incendiary into the air to see how it flies. he references ‘critics’ and ‘enemies’ often, flashing a smile when recalling memorable spats. He relishes a battle of wills. a scuffle of philosophies. And above all, a challenge.

A good place to start if trying to understand Reinhold Messner is to read his 1967 essay, The Murder of the Impossible. It’s passionate, loaded stuff – a rant against what he calls a ‘pollution in the pure spring of mountaineering’: the use of artificial aids in climbing. Example: “Faith in equipment has replaced faith in oneself. ‘Impossible’ doesn’t exist anymore. The dragon is dead, poisoned. Today’s climber carries courage in his rucksack.” It’s signed off with an invitation to action: “Put on your boots. I’m not going to be killing any dragons, but if anyone wants to come with me, we’ll go to the top together.” Bold, but ostensibly lies: dragons were killed.

The first to howl beneath Messner’s axe loud enough for the world to listen was the north wall of Les Droites, scariest ice wall in the Alps, with a record ascent of 3 days. Messner did it in 7 hours, solo, unroped, “like the birds fly, straight up”. Eiger north Face: 10 hours, half the previous best. Nanga Parbat: first solo ascent of an 8,000m peak. Everest, first ascent without oxygen. Everest again, first ascent alone. First to climb all 14 8,000m peaks. The seven summits. The Poles. The deserts, alone. Given this essay, this is his great irony: to the world, he did murder the impossible. Written at 23, I ask him what reading it is like today.

“Now, the article is maybe a little bit puberta, how you say? I was very young, and tell it in the language of a wild young man. But the basic philosophy is still the same. It was about rock climbing, but the same philosophy I brought later, climbing 8000m peaks without oxygen.”

Reinhold’s high-altitude career didn’t start well. Installed on a German expedition to Nanga Parbat in 1970 with his brother Günther, following confusion with his other team members Reinhold ended up setting off alone for the summit via the 8,126m peak’s deadly, unclimbed rupal Face. Günther sprinted after him, catching up just below the summit and exhausting himself in the process. Summiting together, the brothers were benighted, then – after miscommunication with other team members – were forced to descend down the mountain’s remote Diamir Face. Reinhold made it down first. Günther never arrived.

Starving and frostbitten he searched, finding only avalanche debris. Günther was dead; the tragedy would haunt Reinhold for decades. Blamed by his father and the expedition leader for not bringing his brother home, he also lost most of his toes to frostbite. Many would have cut their losses and stopped. Why didn’t he?

“For me Nanga Parbat was the hardest, not just because of the climb but the circumstances. I had a lot of stopping from the parents and the [other] brothers. But I realised I could not change the situation with my brother.”

Reinhold’s injuries meant he would never again rule pure rock-climbing. So he shifted gear. “I became a specialist in high altitude. I could combine my climbing abilities with this different dimension. We had stiffer shoes; toes or not, it didn’t make a difference.”

The gruesome fallout between the members of Nanga Parbat 1970 is complex. Reinhold’s hatred of nationalistic authority, an ambition which was probably interpreted as arrogance, egotistical rivalry between the other climbers (and the fact that Reinhold later eloped with the wife of the member who most staunchly supported him) meant that many expedition members had little love for the Italian by the time the dust settled. Their resentment came to a head in 2000, with books and a publicity flurry promising the ‘truth’ about Nanga Parbat: that Reinhold consciously plotted to abandon Günther for his own glory and sent him back down the rupal Face to almost certain death. Messner’s reaction was rage-filled, and typically blunt: “no man could leave his brother behind to die.”

Given his knack for raising hackles, it would be very easy to see Günther’s death as an excuse for enemies to open fire on Reinhold. That the team members waited 30 years until he was rich and famous to publish ‘the truth’, as they call it, smacks more of envious sensationalism than revelation. It isn’t hard to die on Nanga Parbat; the assertions smelled of bitterness, based on the presumption Reinhold had to have caused his brother’s death purely because he was disagreeably ambitious. History would win.

There’s a dark interplay among many elements of Reinhold’s life. Staring blankly from a bluff within his Firmian museum against the rainy afternoon sky is a wire cameo of A F Mummery, British alpinist, and one of Reinhold’s influences. Mummery disappeared on nanga Parbat, as did Günther Messner. George Mallory is another fascination – also lost at height amid controversy, on Everest, in 1924. Mallory’s body was found in 1999, his old boot – which Reinhold wants to own – a sad, material epitaph.

In 2005, Nanga Parbat also gave up symbolic remains. DNA tests on a boot and pieces of bone Reinhold smuggled out of Pakistan proved they were Günther’s, the location of their discovery vindicating him. Today the boot is a voyeuristic object of curiosity, standing in state in Firmian’s museum, a plaque stating ‘in history, truth always wins’: as close to a two-finger salute to critics as taste will allow him. Messner’s five mountain museums, like his climbs, are beautifully executed by a man who is a slave to nobody’s vision but his own. Each given a theme, they are less art houses than art themselves: near-tantric immersions into the world of the climber, of mountain people and of mountains. They’re design triumphs full of fascinating relics – but you won’t learn a lot.

“These are not museums of me,” he dismisses. “A museum of me would be successful for a few years then collapse. I am using my experiences, but using others’ faces, equipment and so on. These museums are of the relationship between man and mountain. This is very important.” Secreted in the walls of the stunning Firmian museum are prayer flags, religious statues and monuments to holy mountains. Later i ask whether all the spiritual connotations – from the Tibetan Xi stone he wears, to his iconoclastic objects – mean he is superstitious?

“No. I respect cultures, but I’m not trusting a religion, or some black stuff. My instincts brought a possibility to go further than others. I had an interest in following nature, and not technical possibility, on logical, elegant climbing lines. It’s mathematical.”

Reinhold loves maths; he used to teach it. And while his philosophy speaks eloquently of determining limits, respecting ethics and using them to ‘know himself,’ in the end, his physical approach to the mountains is a simple matter of calculation.

Following Nanga Parbat, Reinhold paired up with Austrian Peter Habeler and began obliterating alpine speed records – and 8000m peaks. Gasherbrum i was the first of these to ever be climbed in fast, committing alpine style – without oxygen, of course – in ’75. In ‘78, Reinhold made another first: an 8000m peak ascent utterly alone. The mountain, symbolically, was Nanga Parbat. Surprisingly, Reinhold admits to being afraid alone – but also says that after the tragedy of his brother and the loss of two team members on Manaslu in 1972, being solitary wasn’t just the next step on the challenge ladder: it was psychologically a relief. “Climbing with a partner is the best thing you can do. But I can’t carry the responsibility for others. it is too dangerous.”

He and Peter Habeler stunned the world in 1978, when they made the first ascent of Mount Everest without extra oxygen – ‘by fair means.’ The rules said it was impossible. Again, to Reinhold, the rules meant nothing.

Then came, according to Into Thin Air author John Krakauer, ‘the greatest mountaineering feat of all time.’ during the monsoon of 1980, Reinhold climbed Everest again without oxygen – solo. on his return, when asked why he didn’t take an Italian flag to the summit, his answer drove his anti-nationalistic stance home with typical red-rag unsubtlety.

“This I didn’t do for south Tyrol, for Germany, or Austria. I did it for myself.” At that, he withdrew his handkerchief: “This is my flag.” interviewed for Vanity Fair in 2006, he was quoted more bluntly: “Nature is the only ruler. I shit on flags.”

That evening, we watch a preview of a new film made about Reinhold’s life. It’s lavish, interspersing dramatised key climbs with archive footage. Reinhold and his brothers were involved, but didn’t make it. Afterwards, I ask him what it was like seeing his life, replayed on screen.

“It’s not like memory. Just an interpretation. But [the director] did a good job. It helps my family… understand more.” In the film we see modern Messner walking casually but slowly across the snowy Dolomites summits to Dylan’s The Times They Are a-Changin’. It’s oddly touching: a man defined by withstanding physical limits, now constrained by one even he can’t fight: age.

“When I was young, I would look to the mountains and see this, maybe try that, go there. Now I see them in equilibrium, because I know I can’t do these things.” But against the odds, he’s still here. Luck?

“Not strongly. An extreme adventurer based on luck is not surviving long. The game climbers play is simple – we go freely to a place where you could die, to not die. And since dying is a possibility, surviving is an art.”

There’s more to it than surviving. He needs to be the top of his game at something. It would explain his fidgeting from one challenge to another over the years once he has trounced the other guy: Reinhold the Climber, Mountaineer, Polar Walker, Green MeP, Curator, author (60 books and counting, many of them very good and intensely introspective) and now, it would seem, Reinhold the Filmmaker. He is making a film about the late Walter Bonatti, another figure who, like himself, exhibited genius abilities and was the victim of a smear campaign: in Bonatti’s case, an accusation of sabotage on K2’s first ascent in 1954.

We sit for dinner, drink a lot of local plonk, and – like a deflating puffer fish – he relaxes. The guard drops and, finally, I discover a bit about his most elusive incarnation: Reinhold the Bloke. A sense of humour appears. I hear about the last material possession he sold to finance his solo ascent of Everest – a red Porsche 911 – and that he had one of the first Audi Quattros, before clarifying he was never a ‘sportif’ driver.

He doesn’t watch TV. He carries a battered phone with a cock-a-doodle-doo ringtone. With his wife and his children, he spends the winter in the city and the summer in his castle – Juval – which is also one of his museums.

Simon, one of four children Messner has, is a “better climber than me,” he says. I ask, knowing the dangers, what it is like to see his own son leave for a climb. “We’ll talk about a route he’s doing, and I’ll say ‘you know near the top, there is this bit, and it is difficult here…’ and he will just say ‘Dad – I’m 20.’” has fatherhood changed his outlook?

“Yes, a little. But an adventurer has to make this cut and say: now I am going, and hopefully I will come back. It would be crazy to say ‘Because I am Messner, I-will-not-die.’ There is a risk to die. But [paternal] responsibility is there.”

We talk books. He likes Hemingway, who he says: “came across as very macho. But he was quite sensitive.” Beating me to it, he adds: “I don’t see any parallels. If ever get to that point… I have said to my wife, I will just disappear.”

While we’re on the subject of death, there is another thing he is sure of. “I will not die in the mountains. I have fought a lifetime not to. This is to totally fail. I’ll walk a hundred miles first.”

You see parallels with Muhammad Ali: both articulately opinionated, both damaged by their sport – and both justified in their trademark immodesty and a near-pathological aversion to authority. Interestingly – as defined by doctors after his first Everest summit – Reinhold is physically nothing special; he’s simply a man unbothered by rules, augmenting an unremarkable physiology with remarkable wings of self-belief.

He speaks of his respect for Mallory, and troubled Scottish climber Dougal Haston – who he met in a bar beneath the Eiger during the filming of The Eiger Sanction in 1974. “That was funny. Clint Eastwood shut down filming as the weather was so bad. That day, Peter and myself,“ he points a finger at the ceiling. “Eiger north Face, ten hours.” He chuckles. “Fun night in the bar. I liked Haston. People said he was hurting, but I liked him.”

John Cleare, movie cameraman, recalls the occasion: “It inspired us, and I’d include Clint, to know there were real climbers out there, and we weren’t in a make-believe world.”

And so. a final chance to chat. Noisy geese, flies, crotchety mountaineer. Reinhold the Public Figure is crotchety at times – can you blame him? Get famous enough and you probably have to do all sorts of things you’d rather not be doing. Like talking to magazines.

The life of Reinhold, while not make-believe, is certainly now approaching the status of myth. in 1999, American alt rock band Ben Folds Five released an album entitled The Unauthorised Biography of Reinhold Messner. The cover featured an image of a vaguely Germanic figure multiplied many times, as if in a hall of mirrors. The band claim they used the name on fake IDs as kids, and had no idea they had christened their album after a person who actually existed, whom they later thanked in the liner notes.

Reinhold Messner nods when I ask him if he’s aware of this. “I know. They didn’t think I was real.” He pauses, before adding with a smile: “Maybe I’m not.”

Words and Pictures Simon Ingram © Trail Magazine, October 2012