Tale of a Tall Tale

It was the account of an impossible endeavour: to ‘place two men on the 40,000½ft summit of the highest mountain on Earth’. Sixty years on from its first publication, Trail uncovers the story – and legacy – of the greatest story that never happened.

Simon Ingram / Trail Magazine, 2016

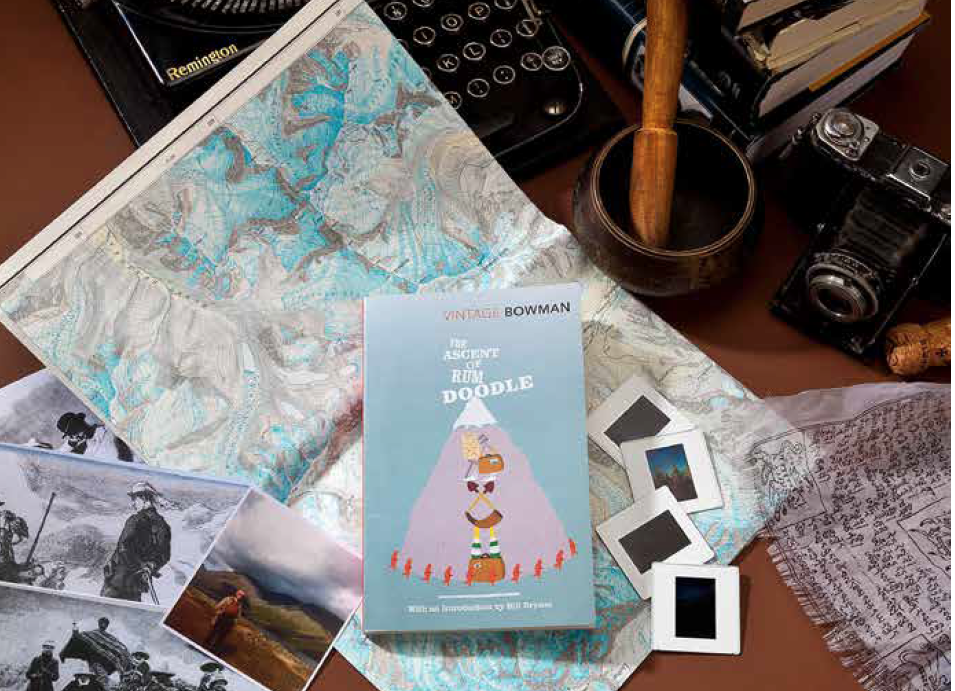

Photograph by Jacques Portal

DEEP in the aromatic chaos of Kathmandu is a bar where mountaineers come back down to earth with a clink. Here explorers rub shoulders with tourists in the heart of this mystical, mountain-ringed city. Climbing the walls is the biggest collection of Everest summiteer signatures in the world. Messner, Hillary, Tenzing, Bonington – all have pulled up a stool beneath this pagoda and scrawled their name for generations to see.

But what of its unusual, evocative name? Rum Doodle. You can find it in other places, too. On a mountain in Antarctica. A ridge in the Rockies. A long-forgotten board game. A folk band. A Lakeland B&B. Coincidence? Nope.

All name-check an obscure British book written by a straight-talking civil engineer from Yorkshire who never climbed higher than Ben Nevis. The book turned 60 in 2016 year. And how a complete piss-take of a mountain expedition – and the quiet genius who wrote it – achieved world reaching influence is a story in itself.

PART I: HIGH

‘To climb Mont Blanc is one thing; to climb Rum Doodle, as Totter once said, is quite another.’

Three years after the first ascent of Everest a slender book emerged onto bookshelves.

It sat among many others that looked rather similar. Annapurna, Maurice Herzog’s epochal tale of hardship, crumbling fingers and the first 8000-metre peak ever climbed; the Wagnerian Nanga Parbat Pilgrimage, by Hermann Buhl; and stiff imperialistic adventure at its best in The Ascent of Everest, by Colonel John Hunt. In this context, a book jacket with a black-and-white etching of a man balancing on a ladder in an icefield was nothing odd.

Not even the overly jaunty lettering of the title gave it away: The Ascent of Rum Doodle, by an unknown writer named W E Bowman. Anyone who looked inside would find all the lunacies of Himalayan epics. The vertiginous peak. Starchy Forewords and Prefaces by squires of the mountaineering establishment. A team, bristling with speciality talents. The strategy, the approach, the dogged crawl into the history books. Except here, lunacy was nudged over the threshold into parody.

Just how far over that threshold depended on just how close to the subject you were. The cast: Jungle (navigation), unable to find his way around London and likely to walk in a circle on glaciers; Shute (photographer), capable of capturing immortal images but almost always accidentally destroying them; Constant (diplomat and linguist), whose mishandling of the local dialect results in near war with the porters; Burley (lead climber), constantly too exhausted to leave his sleeping bag; Wish (scientist), preoccupied with tracking down the Atrocious Snowman and the Himalayan Warple; Prone (doctor), a hypochondriac who contracts everything available. And, narrating it all, expedition leader Binder – a relentlessly optimistic twit quite unprepared to say a word against anyone, even if they clearly deserve it.

The prize was Rum Doodle itself: dreadful and mighty, standing at 40,000ft above the kingdom of Yogistan. “The massif is in the shape of a reversed letter M,” describes Binder in Chapter 2. “The summit comprises two peaks: Rum Doodle itself, and North Doodle. North Doodle lies to the west of the true summit.”

What befalls the team on their way to its top are familiar elements of any Himalayan epic: porter disputes, bickering, dreadful food, an array of high camps, the disappearance of team members. But all have their absurdity magnified to create comic gold.

Everyone has a favourite bit, be it Binder’s determination to have emotional conversations with each of his expedition members about their fiancées; the gravitas given to Totter’s oft-quoted, completely vacuous phrase about Mont Blanc, à la Mallory’s infamous “Because it’s there”; the efforts to escape the lethal cooking of the camp chef, Pong; the ‘medicinal’ abuse of the champagne supplies, and so on.

“The gullibility of the narrator is beautifully judged,” says Andrew Gilchrist, deputy arts editor of The Guardian. “He’s happy to agree to send down champagne to groups of climbers who have fallen down holes, to keep their spirits up. This is a tremendous example of ‘dramatic irony’ – when the reader knows something the narrator doesn’t – and it’s a tough trick to pull off.”

The book’s use of obscure – but genuine – vintage mountaineering images captioned with lines from the text also served to heightened the book’s silly walk between true mountaineering and madness. “The whole book feels like the best of Monty Python,” continues Gilchrist. “That clipped, dogged English bulldog buffoonery was a frequent target of theirs – I’m surprised they’ve never attempted to film it.”

PART 2: AS HIGH AS MOST

“The equipment had to be carried to the railhead at Chaikhosi, a distance of 500 miles. Five porters would be needed for this. Two porters would be needed to carry the food for these five, and another would carry the food for these two. His food would be carried by a boy. The boy would carry his own food. The first supporting party would be established at 38,000ft with a fortnight’s supplies, which necessitated another eight porters and a boy. In all, to transport tents and equipment, food, radio, scientific and photographic gear, personal effects and so on, 3,000 porters and 375 boys would be required.”

The Ascent of Rum Doodle received lavish but limited praise. Almost all reviews referred to the book as an antidote to the recent avalanche of poker-faced mountaineering epics the reading public had clearly had enough of; a satire seemed inevitable. One review – in the Glasgow Evening Times – even began with the words: ‘It’s happened!’ “It’s written so well it is not immediately noticeable as a farce,” wrote Good Housekeeping. “An excellent, badly needed joke,” said the Irish Press. “Yes, but would Hillary approve?” wrote The Times, noting that it was lucky Everest’s recent hero was now too far away to come ‘stalking home with his ice axe’ in search of the book’s author.

In this unlikely event, Hillary would have been lucky to find Bowman. The book carried no biographical material. Some were so convinced by its wise, layered jokes they were convinced the name had to be a pseudonym of a real Himalayan mountaineer – with one reviewer going so far as to name Everest 1953 team member Wilfrid Noyce as prime suspect.

But William Ernest Bowman was quite real, and in many ways no less interesting. “I think he was a kind of old English eccentric,” remembers Ghee Bowman, the author’s son. “He was born in 1911, so was 50 years older than me – so my view of him was quite strange for a son to a father. He had a sense of fun. But he was quite shy, and quiet.”

Scarborough-born, Bowman was a keen walker and sometime climber – he scaled Napes Needle in 1932, and often visited Torridon and the Lake District. Stationed in Egypt during World War Two, he later became a pacifist and made a career in civil engineering, while writing and working quietly away on, among many other projects, a reinterpretation of the theory of relativity. In his papers is a letter of critique from Einstein himself.

“That was in many ways his life’s work, working on relativity,” says Ghee Bowman. “He loved precision and accuracy, and was very analytical. But he also painted, and played piano. He wasn’t a believer that you had to be either an artist or a scientist – he thought humans could be both. And he was an adventurous walker, for sure. He liked to do things just to see if he could.”

Ghee Bowman, now in possession of his father’s journals, cites one trip to Helvellyn where he climbed the mountain three times from Wythburn non-stop. In 1957, aged 46, Bowman climbed all English 3000ers in 15 hours, entirely on foot. “I think the Lake District was his favourite place. What I think is interesting is that he wrote this book about Himalayan climbing, which is something he never did. I think he wanted to be a writer and was engaged in writing for a long time, but the rest of his work was about other things. It was a bit of a detour.” Detour or not, Bowman had hit on something. All who read Rum Doodle thought it hilarious. Climbers too – but perhaps for reasons closer to the truth. After its initial flourish, and translations into several languages, the book began a descent into respectable obscurity. But it remained something of an underground talking point among mountaineers who – remarkably, considering the author’s Himalayan experiences were entirely second-hand – found a deeper truth in its pages.

“Climbers might tell you that it was always there for climbers,” says Ghee Bowman. “I wouldn’t call it a ‘cult’ climbers’ book. It’s got a much more general appeal. But I think the appeal for climbers is perhaps different to the general public. I’d be interested to know what someone like Doug Scott thought about it.”

The joint first Briton to climb Everest happens to have a copy to hand when Trail calls to ask just that. “Oh, it’s wonderful. The perfect satire of a big expedition,” says Doug Scott. “Those characters are fragments of people you come across… who all have their moments of pretentiousness. [Bowman] hit the nail on the head so many times with that. That British understatement, and confidence… It catches the flavour of incidents on all my expeditions. I was belly-laughing at times.”

Chris Bonington – probably the last exponent of the large, siege-style British expeditions to the Himalayas the book satires – agrees. “It’s essential reading for all climbers, particularly for ones who take themselves and their sport too seriously,” he says. “I love it.”

Robert Macfarlane, mountaineer and author of Mountains of the Mind and The Old Ways, cites Rum Doodle as formative to his fascination with mountains; as a child he had found a copy in his grandparents’ house in the Scottish Highlands. “What Bowman taught me early was the deep-down silliness of climbing. All mountaineering is shadowed by absurdity.”

Macfarlane describes an expedition he mounted in his twenties to the Tian Shan [central Asian mountain range] with a view to making a first ascent. “We got heatstroke, frostnip and food poisoning. We got lost on the glacier, and took half a day to travel a mile. Altitude sickness clobbered me so hard my body was used as a card table. We couldn’t have come much closer to re-enacting Rum Doodle.”

PART III: HIGHER THAN MOST

“Jungle, you fool! You’ve been and gone round in a circle!” Shute had gone on filming on the glacier without identifying us as we passed, and we’d all gone around twice. I decided the occasion was suitable for a halt, and over a glass of champagne we discussed the reasons for the mistake.”

WE Bowman’s second book, The Cruise of the Talking Fish, didn’t achieve quite the same acclaim as its predecessor. A third was shelved when publishers Max Parrish fell into difficulty. Bowman continued work as an engineer, writing to his whims in his spare time until his death in 1985.

Ghee Bowman: “When I was growing up, Rum Doodle was just something that was there in the background. In many ways it was his great success, and I think he was attached to it – but he moved on from it.” The book fell out of print till Geoff Birtles of Dark Peak Publishing ‘rediscovered’ it in 1978, and republished it. “That led to further republishing later on,” says Ghee Bowman. “But it didn’t really take off until Bill Bryson.”

It was in 2001 that The Ascent of Rum Doodle received a boost from the best-selling American-born travel writer – who at the height of his own success wrote an introduction to a new edition, claiming it to be one of the funniest book he’d ever read. He still thinks so.

“I was just taken by the title; it sounded intriguing,” remembers Bryson, who first came across it at a charity book sale while working on The Times. “When I saw it I thought it was a serious account of an actual expedition. Very few times in my life have I been so captivated and totally charmed by a book so quickly. It remains one of my very favourite books of all time.”

Bryson – who wrote the best-selling humorous travelogues A Walk in the Woods and Notes from a Small Island – claims the book was one of his last great cultural discoveries after settling in Britain in 1977.

“It’s very easy to parody something by just exaggerating it or making fun of it or just being kind of nasty. Really good parody I think is kind of admiring and affectionate, and with Rum Doodle you can tell that Bowman really loved that kind of book, but he was also able to see the ridiculousness of it. And the very best parodies would be those where you wouldn’t be entirely sure if you were seeing the truth or not. They come so close to being lifelike… a great example would be [TV mockumentary] The Office. I can remember watching that for the first time… I’d just come in from the pub and I put the telly on, and remember thinking for the first few minutes, ‘Is this real…?’ because it was just so well done.

“The part where I realised the book was going to be very funny and also very original was when the expedition members were being described, and after each was ‘he had been high,’ or ‘he had been higher than most’… there was just something about that was so real-seeming, and yet so comical. Sustaining humour over the length of a book is really, really hard. I do think this was a work of genius.”

“I’ve been climbing – mostly the big peaks of Scotland – with the same bunch of guys for about a decade and sometimes Rum Doodle didn’t feel like a spoof at all,” continues Andrew Gilchrist. “I read it thinking: ‘That’s us!” We’ve lost the way, we’ve lost each other, we’ve run out of food, we’ve ended up at the top of the wrong mountain. We do eat better, though – the bits with Pong, the dreadful cook, are very funny.”

Bill Bryson: “The part where I laughed the loudest – howling with laughter – was when Pong came on the scene, because everyone is so obviously terrified of him. His name just told you everything, yet sounded genuine at the same time.”

EPILOGUE: HIGHER THAN ANYONE

“The porter halted, waited for him to come up, then flung him over his shoulder and went on again. Prone, quite demoralized, made himself as comfortable as he could and fell asleep. He was given food and his personal equipment was brought to him. And they kept hard at it, day after day, until they reached the summit. Prone said that he had never been so miserable in his life. The things he had endured, he said, would make a strong colonial turn pale by the mere telling. Rum Doodle was a far stiffer mountain than he had dreamed. He was carried the whole way by the same porter, whose name was Un Sung.”

Despite high-profile supporters, reissues by prestigious publishers and text that reads as crisply today as ever, The Ascent of Rum Doodle remains relatively unknown. But among the mountaineering community, affection for the book and its mythical mountain has steadily appended itself to a remarkable array of tributes.

“There was a [board] game, which sort of brought about the first republishing in the late 1970s. My father knew about the restaurant in Kathmandu, and he was pleased about that; someone sent us one of the cardboard feet people write on,” remembers Ghee Bowman. “And he was sent some photos of the mountain in Antarctica, which was named by an Australian party. He framed them. They’re not particularly good photos and it’s not a particularly big mountain. But nevertheless it’s a real mountain named Rum Doodle. He was pretty chuffed about that.”

And the tributes continue, too – with perhaps the most affectionate the Rum Doodle B&B that opened in Windermere in 2010. Its nine rooms are each named after a character in the book including, inevitably but rather bravely, Room 3: Pong.

For Rum Doodle to still be in print 60 years on is one thing; to achieve true worldwide success – as Totter might have said – is quite another. And perhaps the funniest mountaineering book of all time will forever be enjoyed mostly by mountaineers. “It does make you feel special when you know about something the rest of the world doesn’t,” says Bill Bryson. “But at the same time this book could bring so much delight and joy to so many people who are missing out. And it is a perennial mystery and frustration to me why the world doesn’t embrace this book in a big way, because it totally deserves it.”

Simon Ingram © Trail Magazine, October 2016